Women’s Magazine – February 2004

Women’s Magazine – February 2004

By Marcey J. Cote

Some might expect an astronomer to have his eyes locked on the sky or his head in the clouds, but Jeffrey Bennett defies these stereotypes. While the local astronomer/writer uses his academic background to drive his personal mission, he keeps his ideas firmly grounded. His ideas about the connections between our daily lives and the universe are compelling.

Bennett is guided by his belief that our civilization is at a critical point. He’s concerned that problems such as environmental degradation, explosive population growth, and losses of individual freedom are related to a lack of understanding. He fears that our ignorance of the relationship between humanity and the natural world could be our eventual downfall.

“The earth is a very tiny planet. When you come to understand how truly tiny it is, you’re either faced with thinking we, as humanity, are completely meaningless, or figuring out how you can be meaningful. And it’s not too hard to come up with ways to make your existence meaningful,” Bennett says.

Spoken like a pro, Bennett has no problem making a meaningful existence. An “astronomer by training and a teacher by trade,” Jeff’s ideas have reached many. He’s taught numerous classes at CU, covering everything from astronomy to physics to mathematics. He’s run private science summer school classes for young children. For two years in the early ’90s, he worked at NASA creating education programs.

Staying true to his mission of education, Bennett spawned the idea for Voyage, a modular solar system on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Voyage, which opened in October 2001. Voyage depicts the Sun, the nine planets, and the distances between them. Visitors can walk from planet to planet, gaining a more tangible perspective of the vastness of our solar system. A similar model, also by Bennett, is on the CU campus, beginning with the sun module outside Fiske Planetarium.

Staying true to his mission of education, Bennett spawned the idea for Voyage, a modular solar system on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Voyage, which opened in October 2001. Voyage depicts the Sun, the nine planets, and the distances between them. Visitors can walk from planet to planet, gaining a more tangible perspective of the vastness of our solar system. A similar model, also by Bennett, is on the CU campus, beginning with the sun module outside Fiske Planetarium.

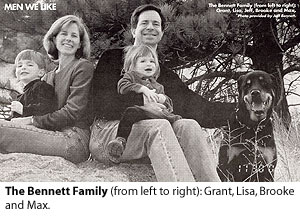

Now, having transitioned out of the “official” teaching world, Bennett spends most of his time writing. He’s written several books in the science field, including college texts. Most exciting to Bennett, however, is his first children’s book, Max Goes to the Moon, which was published in spring, 2003. The story features Max the dog, and his friend Tori, on their quest to travel to the moon with NASA astronauts. The story ends on an inspirational note, underscoring Bennett’s passion for educating ourselves about our planet and the universe around us.

Women’s Magazine had an opportunity to talk with Bennett about his passion for the planet and his vision for humanity.

WM: Has your career changed your perspective on earth and humanity?

JB: To me, the biggest first success of our species is that out of this gigantic universe of which we’re a tiny part, we’re also – as far as we know – the only tiny part that knows the rest of it exists. That’s a pretty amazing accomplishment for something as small as us. No matter what your religious point of view, if you look through history, religion has always been about attaining self-awareness – however you go about it. If you want to be self-aware, you need to be aware of your surroundings.

WM: What’s the most important thing for us to learn about our relationship with the natural world?

JB: We need to know and understand that we’re not the center of the universe. I wrote something at one point about COTUS, which stands for Center of the World Syndrome, which is what I think many people suffer from. There are lots of ways to get over it, but mostly it’s doing things like learning about the scale of the universe, looking at pictures we get from the Hubble telescope and seeing that the moon and Mars are places you can walk on.

WM: What’s your biggest hope for humanity?

JB: You have to be an optimist or it’s no fun. One of my favorite quotes is from HG Wells who says, “The future of our civilization is ever more a race between education and catastrophe.” So I’m going to work on the education side of that and hope we avoid catastrophe. Changing behavior is hard to do, but when people are educated, they can change their own behavior. It’s a daunting task, though, even in this country.

WM: Is our education system doing enough to help people learn about space?

JB: The U.S. tries. I’d give us an A for effort, but maybe a lower grade for actually carrying out what we’re taught. But I think people are trying; that’s why I’ve put my efforts there. The biggest thing is having the materials out there. In elementary school, for example, most kids have a section on astronomy. But once they get out of school, there isn’t as much available.

Also, educating women around the world is more than half the battle because women make up more than half of the population. You can’t leave half the world uneducated if you want to make a difference.

WM: What do you think of the recent buzz from washington about Reinvigorating the space program?

JB: I’m happy to say that this is a question that transcends politics, and I think that whether you are conservative or liberal, it should be clear that reinvigorating our space program is crucial to our survival not only as a nation, but also as a civilization. My only caveat on the Bush proposal (first a permanent base on the Moon, which would then become a stepping stone to Mars) is that it must be done as an international, collaborative effort — not as a go-it-alone American venture.

Of course, some people will argue that the dollars are better spent dealing with problems here on the ground, but economists are virtually unanimous in judging that every dollar spent on the civilian space program has returned several dollars to our overall economy. Thus, rather than depleting our resources for solving other problems, the investment in space actually increases the available resources.

Perhaps even more important, I believe that a permanent base on the Moon would be of priceless inspirational value to people everywhere. If the base is truly international, as it should be, there will be people from virtually every nation working together on the Moon. Every child, whether in the U.S. or Iraq or Egypt or China, would be able to look up at the Moon in the sky and know “There are people just like me living and working there right now.” I don’t want to sound like I’m wearing rose-colored glasses, but I really do think that this inspiration could change the way people behave toward each other around the world.

Copyright, Women’s Magazine