Updated: June 22, 2001

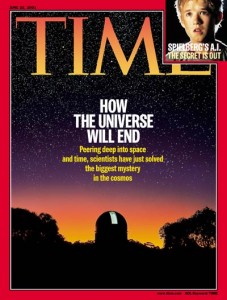

At any newsstand, you can see astronomy hitting the mainstream media on the cover of this week’s Time magazine (June 25, 2001). The cover reads:

At any newsstand, you can see astronomy hitting the mainstream media on the cover of this week’s Time magazine (June 25, 2001). The cover reads:

How Will The Universe End?

Peering deep into space and time, scientists have just solved the biggest mystery in the cosmos

Well, on my personal Top 10 list in On the Cosmic Horizon, the question of the fate of the universe ranked as Mystery #3, meaning that I disagree that it’s the “biggest mystery in the cosmos” — though it certainly ranks up there. But more to the point, has this mystery really been solved?

First, let me say that the Time article is very well done and well worth reading. Moreover, while the cover claims the mystery solved, the article itself is much more cautious. That’s good, because the mystery is not solved. In fact, nothing fundamental has changed since I wrote Mystery #3, other than that the tentative evidence that caused me to rank the mystery so high on my list has been greatly strengthened by more recent discoveries. That is, the new discoveries covered in the Time article have only deepened the mystery. As usual, I encourage you to read Mystery #3 for background that will help you understand the Time article. Meanwhile, here’s the brief synopsis:

Recall that the universe is currently expanding, but that gravity opposes the expansion by trying to pull matter back together. Until about 5 years ago, most astronomers assumed that fate of the universe therefore rested solely on the overall strength of gravity, which depends on the total density of matter in the universe. If the density turned out to be large enough, gravity would ultimately win out over expansion and the universe would eventually collapse and end in a “big crunch.” If the density turned out to be too small, gravity would slow the expansion but never stop it, and the universe would expand forever.

By a decade or more ago, evidence was already mounting that the density of matter (including the mysterious dark matter; see Mystery #2) is too low to ever stop the expansion. Thus, it seemed that the fate of the universe would be to expand forever. In fact, the evidence for the “too low” density of matter was so strong that the fate of the universe might not even have made my Top 10 list of mysteries. Then, beginning in about 1997, a serious wrench was thrown into the entire issue by new observations intended to measure how much the expansion was being slowed by gravity. Instead of measuring the expected slowing, these observations suggested that the expansion is accelerating. The only way to account for such an acceleration is to presume that the universe contains some type of mysterious energy, now called “dark energy” (by analogy to “dark matter,” as opposed to suggesting anything sinister), that fuels the universal expansion.

As recently as a few months ago, many astronomers remained skeptical of the existence of dark energy, largely because it seems so outlandish. (A similar possibility was actually first suggested by Einstein, who later disavowed it as “the greatest blunder” of his career.) However, new measurements — the ones that led to the cover story in Time — have erased most of the doubts. Unless the data are being seriously misinterpreted, the expansion of the universe really is accelerating.

On its face, an accelerating universe only means more nails in the coffin of never-ending expansion. After all, if it was going to expand forever even in the absence of acceleration, the added push would seem only to seal the case. So why don’t I think the mystery is solved? Because I believe the more important lesson from the discovery of an accelerating expansion is that the universe is more surprising than we previously had guessed. If there can be something as bizarre as “dark energy,” then what previously seemed like a simple question with only two possible answers might not be so simple after all.

The fundamental problem is that forever is a REALLY long time. If the universe were as simple as it had seemed just 5 years ago, perhaps we would have been justified in feeling that we could successfully extrapolate current conditions to forever. But in light of the new discoveries, I’ve lost confidence in such extrapolations. Given such an important discovery in the past 5 years, how can we be confident that we won’t discover something equally important to the fate of the universe in 5 years, 50 years, or 500 years? For example, suppose we someday discover that the strength of gravity (i.e., the gravitational constant) can slowly change. Over a time of forever, even a change that might be too small for us to observe directly — say, a change by one part in a trillion every trillion years — would eventually add up and might overwhelm the acceleration. Bottom line: the new discoveries have only confirmed that the fate of the universe should rank as one of the outstanding mysteries in astronomy.

On a related note, the new discoveries also shed some light on the question of whether the early universe had a bout of inflation — the topic of Mystery #4 in my book. The amount of “dark energy” inferred from the current observations is just what is needed to give the universe a “flat” geometry, as the theory of inflation claims it must have. In that sense, the new discoveries offer the first solid evidence for inflation, though this evidence is still quite indirect. However, before we claim victory for inflation, note that some of the same theories that lead to the idea of inflation also can be used to predict that the universe could have “dark energy” of a particular quantum type — but the amount they predict differs from the observations by 120 orders of magnitude (that is, 10 to the 120th power)! As physicist Michael Turner stated in the Time article, this prediction “is the most embarrassing number in physics.” As long as we have no idea what constitutes the “dark energy,” we are in the same boat with Mysteries #4 and #3 as we are with #2 on dark matter — that is, we are lost at sea. This may mean a lot of work for astronomers and physicists trying to sort things out, but it’s at least temporarily good news for me, since it means I don’t need to revise my ranking of these important mysteries.