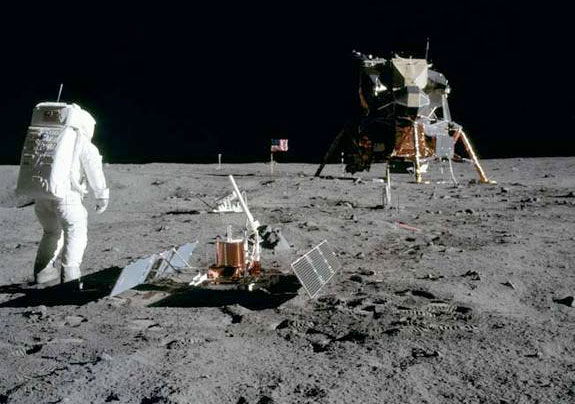

Apollo 11 Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot, is shown here after deploying the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package. In the foreground is the Passive Seismic Experiment Package; beyond it is the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector. A new look at old data spotlights how rocket landings and departures on the Moon can impact equipment. Credit: NASA.

Imagine that you could send a single short message through time to anyone who has ever lived, telling them one modern fact that would give them hope for the future of humanity. I don’t think you could find anything more powerful than this: Human beings have walked on the Moon, and upon first arrival left a plaque that read “We came in peace for all mankind.”

No other single event in human history would be both so understandable — after all, everyone can see the Moon — and so amazing at the same time. For most of history, a trip to the Moon would have been considered impossible. Even once it became possible in principle, few believed that it could really be done. But not only did we do it, we did it in a way that made it belong to all of humanity, not just to the astronauts who made the trip, to the people who built the program, or to the nation that paid for it. Surely, if we are capable of that, it would seem that we are capable of anything.

Or rather that we were capable. For this year marks the 40th anniversary of the landing of Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969. Those of us old enough to remember that day will recall how it riveted attention around the world, even from our enemies at the time. As Neil Armstrong took “one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,” we all shared a brief moment when humanity seemed poised on the brink of a transcendent future.

The success of Apollo 11 was followed by several more trips to the Moon, along with the astonishing rescue of Apollo 13, but it was all over by the end of 1972. We’ve had many remarkable achievements since that time, including the great successes of our robotic probes to the planets and the Hubble Space Telescope, but no human being has again gone beyond low-Earth orbit — a distance barely 1/1000 of the distance to the Moon. The startling truth is that, to scale, the difference between our current human space voyages and the voyages of Apollo is as great as the difference between a walk the length of Central Park and a walk across the United States.

The problems we face today are very different from those we faced 40 years ago. The well-defined enemies of the Cold War have been replaced by the cat-and-mouse battle against terrorism, worries about urban air pollution have given way to worries about the global climate system, and we are in the midst of a global recession. The key to the solutions, however, remains the same, just as it has remained the same throughout history: We need to believe in ourselves, and to inspire and educate our children, so that we can rise above our current problems and build a better future.

That is why I believe it is time for us to recommit ourselves to our future in space, beginning with a return to the Moon. But we must do it in a way that ensures it is the start of greater things, not an end in itself that can fade into memory like Apollo. Unfortunately, NASA’s current plans for returning to the Moon are under funded, lacking in vision, and too parochial. We can do better.

First, we must return to the Moon with a clear vision, and I believe it should be this: To build an international research outpost at which people of every nation, every race, and every religion will work together in pursuit of fundamental knowledge and discoveries that advance the common good, so that every child on Earth can look up at the Moon in the sky and say, “We are working together up there, so surely we can work together down here.” Perhaps a Moon outpost cannot by itself put an end to terrorism, but by providing a constant reminder of the great potential of the human race, it surely can help.

Second, we must commit the resources needed to achieve this vision. Adjusted for inflation, NASA’s funding today is far smaller than it was during the Apollo era. Investments in space have always returned far more to our economy than they have cost, so greater NASA spending can help lift us out of our current economic doldrums. Since the venture should be international, it can help other nations as well. The new program should also provide opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs, because only through private enterprise can we secure a long-term future in space.

Third, we must not wait any longer. In the 1960s, we landed on the Moon barely 8 years after President Kennedy started the Apollo program. With the advances that have since occurred in business and technology, we should be able to do at least as well now.

In the Bible, Moses and the Israelites were forced to wander the desert for 40 years before they enter the promised land. The new promised land is the unlimited frontier of space, and we’ve already had our 40 years in the post-Apollo desert. It is time for us to reclaim the promise of Apollo, and begin down the path that will take our descendents to the stars.